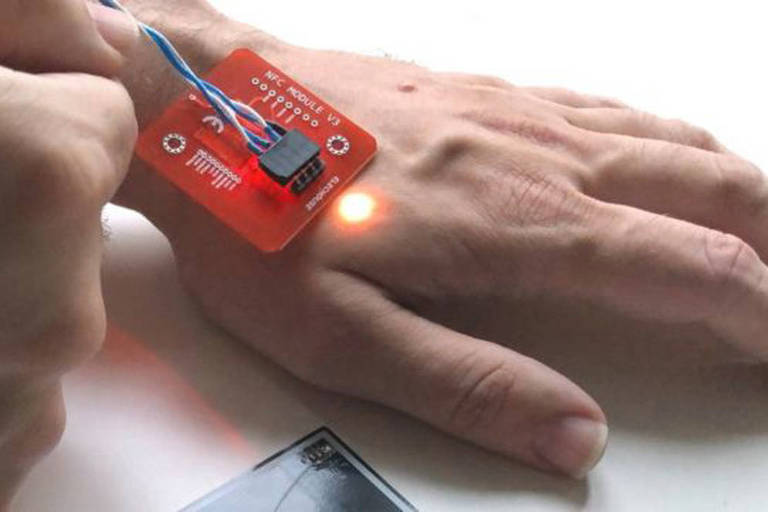

Companies offer chips injected under the skin, which can be used to pay bills

Dutchman Patrick Paumen, 37, causes a stir whenever he pays for something in a store or restaurant.

He doesn’t have to use cash, bank card or cell phone to pay. Instead, he simply places his left hand near the card reader and payment is made.

“The reactions I get from the tellers are priceless,” says Paumen, who works as a security guard. He can afford using only his hand because in 2019 he had a pay microchip injected under his skin. “The procedure hurts as much as when pinching the skin,”

Paumen says.

The first time a microchip was implanted in a human being was in 1998, but it was only in the last decade that this technology became commercially available.

Anglo-Polish company Walletmor says it became the first company last year to put implantable payment chips on sale.

“The implant can be used to buy a drink on the beach in Rio, a coffee shop in New York, a haircut in Paris —or at the local supermarket,” says founder and chief executive Wojtek Paprota. “It can be used wherever contactless payments are accepted.”

The Walletmor chip, which weighs less than a gram and is slightly larger than a grain of rice, consists of a tiny microchip and an antenna slumed in a biopolymer – a material of natural origin, similar to plastic.

Paprota says the chip is fully secure, has regulatory approval and works immediately after it is deployed. It also does not require battery or other source. The company says it has sold more than 500 chips.

The technology Walletmor uses is near-field communication or NFC—the approach payment system on smartphones. Other payment implants are based on radio frequency identification (RFID), which is the similar technology typically found in physical debit and credit cards by approach.

For many of us, the idea of having a chip implanted in our body is horrible, but a 2021 survey of more than 4,000 people in the UK and the European Union found that 51% would consider having an implant.

However, without providing a percentage, the report added that “issues of invasion and security remain a major concern” for respondents.

Paumen says he doesn’t have any of those concerns.

“Chip implants contain the same kind of technology that people use on a daily basis,” he says, “from keychain scans to unlocking doors, public transport cards like the Oyster [London public transport] card or contactless payment card.”

“The reading distance is limited by the small antenna coil inside the implant. The implant must be within the electromagnetic field of an RFID reader [or NFC]. Only when there is a magnetic coupling between the reader and the transponder can the implant be read.”

He adds that he is not concerned about having his whereabouts traced.

“RFID chips are used on pets to identify them when they are lost,” he says. “But it is not possible to locate them using an RFID chip implant—the missing animal needs to be found physically. Then the whole body is scand until the RFID chip implant is found and read.”

However, the problem with these chips (and what causes concern) is whether in the future they will become increasingly advanced and full of a person’s private data. And if this information is secure and whether a person can actually be traced.

Financial Technology expert Theodora Lau co-authored the book “Beyond Good: How Technology Is Leading A Business Driven Revolution.”

She says the deployed payment chips are just “an extension of the internet of things.” That is, it is a new way to connect and exchange data.

However, while she says many people are open to the idea —because it would make paying for things faster and easier—the benefit should be weighed against the risks. Especially as chips start carrying more personal information.

“How much are we willing to pay for convenience?” she says. “Where do we draw the line when it comes to privacy and security? Who will protect the critical infrastructure and the humans that are part of it?”

Nada Kakabadse, professor of Politics, Governance and Ethics at Henley Business School at Reading University, is also cautious about the future of more advanced chips.

“There is a dark side of technology that has the potential for abuse,” she says. “For those who do not love individual freedom, it opens up new and seductive visions of control, manipulation and oppression. And who’s the owner of the data? Who has access to the data? And is it ethical to chip people like we do with pets?”

The result, she warns, may be “the disempowerment of many for the benefit of the few.”

Steven Northam, professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at winchester University, says the concerns are unwarranted. In addition to his academic work, he is the founder of the British company BioTeq, which has been manufacturing wireless deployed chips since 2017.

Your implants are aimed at people with disabilities who can use the chips to open doors automatically.

“We have daily appointments,” he says, “and we have performed more than 500 implants in the UK —but Covid has caused some reduction in demand.”

“This technology has been used in animals for years,” he argues. “They are very small and inert objects. There are no risks.”

In the Netherlands, Paumen describes himself as a “biohacker” —someone who puts pieces of technology in his body to try to improve his performance. It has 32 implants in total, including chips to open doors and built-in magnets.

“Technology keeps evolving, so I keep collecting more,” he says. “My implants improve my body. I wouldn’t want to live without them,” he says.

“There will always be people who don’t want to modify their bodies. We must respect that—and they must respect us as biohackers.”